Editorial: No, We Don't Drive Model Ts Anymore

The debate over how best to address the mounting concerns over the Scajaquada Expressway and Delaware Park invites contribution from all sides: the satisfaction of so many interests groups depends on which course of action the Department of Transportation decides upon. A recent editorial posted on Buffalo Rising offered a summary of the arguments voiced by some of the most active organizations involved in the discussion. The author of the post refuted these arguments, maintaining a position shared by many disgruntled motorists, at least partially on the grounds that efforts to preserve the integrity of Delaware Park “promot[e] nostalgia for a bygone era.” In doing so, this author fell into a injurious rhetorical strategy, one that damages preservation efforts and threatens to doom bold policies to false epithets. Preservation does not simply mean saving old things because they are old. The compelling preservationist uses history as a reference in order to promote time-tested methods and structures for the benefit of the greater community. Preservation and the study of history mean looking backward, not for the sake of nostalgia, but for the sake of understanding. Placing the argument over the fate of the Scajaquada Expressway and Delaware Park as a moment in a series of trends enhances our understanding of the consequences of infrastructure.

Advocates for a solution that promotes the interests of motorists on the Scajaquada frame the narrative as disagreement between obstructionists who relish in an idyllic past which they never experienced and rationalists who live in the modern world. Yet by positing the automobile as a pragmatic necessity, these advocates for a return to the 55 mph speed limit and a preserved infrastructure seem blind to the false paradigm upon which their advocacy depends. The nostalgia for the garden city of yesterday actually embraces principles in accordance with contemporary urban design; the fading plausibility of the city that prioritizes car traffic fails to reconcile the reality of successful urban planning in the twenty first century and threatens to doom Buffalo to perpetual decline. This dangerous dependence on the status quo ignores the empirical nightmare promised by prolonged dependance on the automobile.

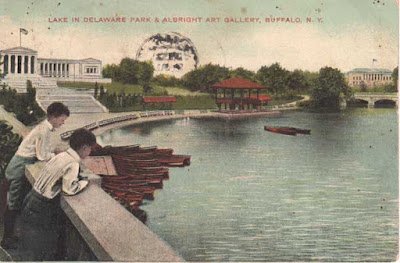

One last glimpse at the park before Urban Renewal...

Courtesy of Buffalo Architecture and History

Yes, the population of Buffalo today still outnumbers that of the city on which Olmsted stamped his design, but examine the numbers from the subsequent decades: after the implementation of Olmstead’s garden city design, the population of Buffalo skyrocketed. According to compiled statistics from the United States Census, it increased from roughly 117,00 in 1870 to 226,000 in 1890 and 352,000 in 1900. During the decades in which Buffalo’s population grew to equal and then surpass its present register, speculators such as Lewis J. Bennet, August Hager, and John C. Cook embraced Olmsted and Vaux’s plan by designing communities around the parks. The greenspace encouraged the establishment of so many neighborhoods that developed strong characters, such as North Park, Central Park, Parkside, and Hamlin Park. Of course a prodigious design for a park system cannot wholly account for the city’s massive growth in the fin de siècle, but ignoring the role that Olmsted and Vaux’s park system played in the meteoric rise of Buffalo shies away from a grand truth about the urban landscape. When city planners design projects to the benefit of the neighborhoods that host them, residents (and prospective developers and home buyers) recognize the harmony.

Olmsted's Garden city, c. 1896, a holistic design that allowed residents to travel throughout the city by way of one network of unabridged greenspace. Delaware Park was not a park within a city: Buffalo was "a city within a park." Courtesy of Buffalo Architecture and History

During the middle of the twentieth century, Buffalo’s population collapsed. Urban Renewal and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 encouraged the construction of the Kensington and Scajaquada Expressways, and the city promised downtown accessibility for suburbanites and easier transportation between the city and the airport. Using the greenspaces created by Olmsted’s garden city plan as a skeleton, the designers of these expressways superimposed their structures onto tree-lined boulevards and cut through a number of neighborhoods. The structural integrity of some of these neighborhoods mostly survived this period of Urban Renewal, but for neighborhoods to the southeast of the park like Hamlin Park, the intrusion of the expressway system threatened to drive property values down and limit mobility and access to greenspace for homeowners. The residents of Hamlin Park demonstrated resilience, not complacency, in the face of Urban Renewal. They had purchased their homes in Hamlin Park before the destruction of Humboldt Parkway; their interests do not fall into the category of selfish speculation, for they have experienced the very real effects of the Expressway System on property values. While the residents of Hamlin Park were able to take advantage of the Model Cities Program in order to avoid deterioration and maintain property values, other neighborhoods on the East Side fared much worse during the Urban Renewal period. Naturally, the Parkside Community Association is not the only interest group voicing concerns about the adverse effects of the Expressway System on their community: Hamlin Park Taxpayers Association and the affiliated Restore our Community Coalition advocate for a rethinking of the Expressway System.

No, we no longer drive Model Ts. We have power steering and V-8 engines. We also have an unfortunate addiction to the fossil fuel lifestyle, and the symptoms of our ailment include profuse carbon dioxide emissions, a degradation of general well-being, and rampant proliferation of automobile accidents, which remain one of leading causes of deathin the United States. Encouraging residents to enjoy the park system on foot or on a bicycle while discouraging the overuse of the automobile for short commutes is just another one of the small steps we continue to turn up our collective nose at, but the untenable attachment to gasoline and convenience threatens to topple our quality of life. If we cannot commit the time and effort to walk through and enjoy the scenery of the park on our way to our important destinations, how will we stand up to the looming catastrophe of global climate change? Of course, reality dictates that commuters continue to have the option to drive to work, but it does not dictate that our authorities engineer our city’s infrastructure to accommodate an unwillingness to adapt to the realities of the looming century.

Ford's Model T, the first ubiquitous automobile, hit the streets in 1908, years after Olmsted planned Delaware Park.

Commuters still made it to work on time.

Courtesy of Wikipedia

Advocates for a return to the 55 mph severely overestimate the efficiency of the high-speed commute. According to the department of transportation, the Scajaquada Expressway measures about 3.59 miles in its current form. Applying the basic equation for speed as a function of distance over time, the amount of time it takes to drive from one end of the Scajaquada to the other at a speed of 55 mph is about 3 minutes and 55 seconds. Given the current 30 mph speed limit, the travel time is about 7 minutes and 11 seconds. That means that the original speed limit saves motorists about 6 minutes for a round trip commute, provided they travel the length of the Scajaquada and encounter no traffic. By privileging 6 minutes worth of an individual's time over the shared benefit of a more accessible and accommodating greenspace, these advocates demonstrate an underappreciation for the physical and economic wellbeing of citizens, the vitality of the city of Buffalo, and the concerns of future generation threatened by carbon emissions.

And no, Buffalo’s winter conditions do not encourage commuters to walk or bike to work year-round, but they also pose a major risk for commuters hurdling down an expressway at white-knuckle speeds. Sacrificing some time out of the day to strap on the winter boots and get some fresh air and exercise might sound laborious, but it pales in comparison to tragedy. The Scajaquada WKBW reported on the recessed rate of accidents following the speed limit recourse, I encourage the skeptic to take a look. The top comment on the aforementioned Buffalo Rising article also provides more general statistics regarding speed limits and safety. Although the prospect of trudging through snow in the early morning might make it harder to get out of bed, the side-effects of a daily commute on foot or on a bicycle outweigh the convenience offered by the automobile. A decision to promote alternative commuting methods by creating the favorable infrastructure encourages residents to make decisions informed by a breadth of factors, not just convenience alone.

Back in 2000, Michael Lewyn published, Car-Free in Buffalo, a guide to getting around Buffalo without an automobile. Seventeen years ago, Lewyn proved that it is possible to live in Buffalo, execute the duties of a professional job, and enjoy yourself, all without a car throughout the entire year. Moreover, he argued that mitigating congestion did not play a role in the economic vitality of American cities. Based on a comparison between the cost of congestion per motorist in specific cities and the rate of population growth or decline in these cities, Lewyn drew a conclusion with resonant ties to our current debate: congestion did not prevent people from moving to growing cities. Seventeen years later, Lewyn’s anecdotal observation still holds true:

“Indeed, common sense suggests that a smooth drive and a smooth economy do not go together. When a metro area grows, new residents flood the existing infrastructure, causing congestion. But when a city withers, the few remaining residents can enjoy a fast ride through deserted streets.”

If authorities devoted taxpayer dollars to revamping our mercurial public transportation system rather than to maintaining and revamping high-speed expressways, and if we could muster the energy to encourage a culture of collectivist transport, we might not have to come to blows over the fate of a highway through the heart of our crowning park. The preservation and restoration of greenspace would come as a no-brainer.

Yes, Delaware Park has its flaws. Urban Renewal severed its tree-lined connection with Martin Luther King, Jr. Park. Most residents would sooner give up their hat than retrieve it from Hoyt Lake or Scajaquada Creek. The golf course dominating the meadow limits use of that space for the occupants of a number of tax brackets. The twentieth century undoubtedly took its toll on Olmsted’s design, but these changes cannot dampen the benefits of accessible greenspace for residents. The fact is, greenspace improves the quality of life for those who have access to it in innumerable ways. Olmsted recognized this reality and strung his greenspaces through not just the most well-to-do neighborhoods in the city, but also emergent middle class neighborhoods like those mentioned above. Adding insult to infrastructural injury, the destruction of Humboldt Parkway failed to recognize the democracy of Olmsted’s placement and tore the most proximate greenspace away from the residents of these middle class neighborhoods. Any decision to further detract from the park or its accessibility threatens to further damage the welfare of residents of all of the neighborhoods bordering the park. Privileging motorists at the expense of residents whose access to greenspace suffocates as a result of the expressway system’s stranglehold on Delaware Park, especially residents to the southeast, asks authorities to perpetuate the “business as usual” methodology that promises the further stagnation of the city’s economy. People do not choose cities based on how quickly they can drive their cars from one end of them to the other; they choose where they want to call home based on the quality of life offered by the places they envision.

How do other cities do it? So many of the most successful cities never opted for expressways through their greenspaces in the first place. Instead, urban planners in cities like London and New York opted for less intrusive beltline expressways and intra-neighborhood public transportation systems in order to ensure accessibility. In many cases, other cities faced equally difficult decisions during the Urban Renewal period, and even cities with economies that survived the twentieth century faced devastating policies and the placement of expressways which detract from their greenspaces. But in all of the cases worth imitating, greenspaces and the value of immediate properties survived. The grandeur of places like Olmstead’s Central Park might never have survived the intrusion of a multi-lane highway through their cores. The preservation of the holistic integrity of successful greenspaces promotes economic growth by ensuring residential stability.

Olmsted's Central Park, still expressway-free. Courtesy of http://www.centralparktoursnyc.com/

I am not a member of any of the organizations which officially oppose the Department of Transportation’s plans or those who endorse any of the proposed quick-fix solutions. It is hard to imagine that changing the value of any number or any of the words scrawled across any of the signs by the side of the road will solve a problem that has festered for decades. I do not fully endorse any single agenda, but I do live here. I love provident design. I love the park system, I love Buffalo, and I love the planet that we all have to share. It pains me to see the discourse surrounding the issue plagued by a false paradigm. Conserving greenspace is not an attempt to live in the past, it is an effort to embrace progress. Calls to curb the selfishness of advocates for a restored park atmosphere lack self-awareness: reaching for a return to high-speed normalcy and sacrificing the wellbeing of the city itself to shave a few minutes off your commute ignores the best interest of Buffalonians in the future and falls into the category of obstructionist romanticization of outdated ideology. It would be foolhardy to return to heating our houses with coal simply because that is how it was done in the past, just as it would be foolhardy to return to the Scajaquada Expressway of yesterday for the sake of the very same sentiment.

A painting of Frederick Law Olmsted. Courtesy of Wikipedia

We talk about resurgence these days as if it is a given, but unfortunately, the numbers disagree: our population still shrinks every year, and the only things standing in the way of Buffalo’s deterioration are deliberate decisions and hard work. Let’s stop designing a city for people who do not live here. Let’s embrace our own historic legacy and engineer a city for Buffalonians to come.